A lot of my work these days involves increasing accessibility in online classes and documents. Most of the documents are Microsoft Word, Microsoft PowerPoint, or PDFs. The online classes are in Anthology’s Blackboard Ultra Learning Management System (LMS). Common accessibility issues across all of these domains are images which lack alt text. To be accessible for people who can’t see or can’t see well, images need brief, relevant, text descriptions which live behind the scenes but can be read out loud by screen reader software. In the public sector, such features are required by law (ADA, Title II), but there’s also an ethical case to be made for their inclusion even when they’re not a legal requirement.

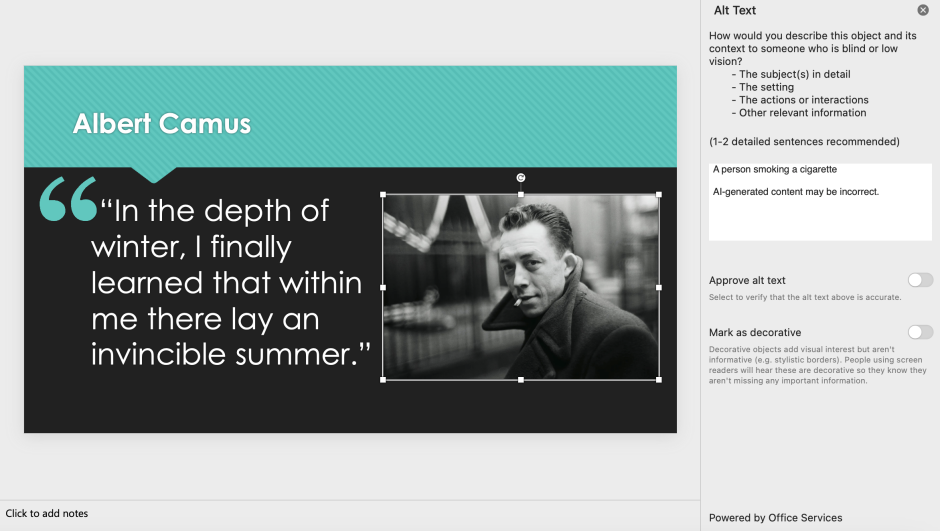

French philosopher Albert Camus (November 7, 1913 — January 4, 1960) cared a lot about ethics, which he explored in his essays, short stories, plays, and novels. I’m a fan of his work, and I’m going to use the famous image of him, taken by Henri Cartier-Bresson (August 22, 1908 – August 3, 2004) in the 1940s, as an example of how alt text works. Take a minute to appreciate his coolness:

If this image were in a file called camus.jpg and included on a web page, the image tag for it, which lives behind the scenes in the code of the web page, might look like this:

<img src="camus.jpg" alt="a black-and-white image of philosopher Albert Camus in a heavy coat, looking over his shoulder at the camera">The code behind a web page is invisible to most people most of the time. You can view it in most web browsers by right-clicking the page and choosing “View source” or “Inspect.” But, unless you build web pages for a living, you’ll likely never want to. However, screen reader software reads the entire page, including a lot of this code that lives behind the scenes and uses it to make the page more useful to people who don’t have the advantage of 20/20 vision.

Obviously, you can write these alt text descriptions yourself. Back in the day, you had to. There’s an art and a science to it. You don’t want to go too long and Dickensian. But being too brief can fail to convey the spirit of the image, cheating the blind and visually impaired. As with most things, context is king. In some contexts (e.g., a photography class), going long would be a requirement. In others (e.g., a magazine article about Existentialist philosophers who don’t like being called “Existentialist philosophers”) brevity might indeed be the soul of wit.

Generative AI can speed up the process. While I don’t want to get into the weeds about the ethics of using AI in this post, I do want to take a moment to acknowledge the problem. To say that the resource consumption of AI tools is concerning is an understatement. For one of many examples which should raise alarm, consider the damage Elon Musk’s Colossus datacenter, which powers his Grok AI, is doing to the air quality in Memphis, Tennessee:

- ‘We Are the Last of the Forgotten:’ Inside the Memphis Community Battling Elon Musk’s xAI

- A billionaire, an AI supercomputer, toxic emissions and a Memphis community that did nothing wrong

However, I’ll bracket the ethical concerns of using AI for the duration of this post. I promise a future post where I discuss it in earnest. But, for now, the prompts have already been run. We might as well examine the data.

Alt text was born on the web. An “alt” attribute is included in the HTML 3.2 Reference Specification (1997), where it is mentioned as a backup value for Java Applets and image maps, technologies nobody uses anymore. It got included for real, in 1999, in the W3C’s HTML 4.01 Specification.

But alt text has found its way into many content creation tools, including Microsoft Word and Microsoft PowerPoint. AI is now baked into these tools as well. But it’s performance, when it comes to alt text is lackluster.

PowerPoint’s AI-generated alt text for the image of Camus was “A person smoking a cigarette. AI-generated content may be incorrect.” The fact that the disclaimer about AI-generated alt text is included in the alt text is particularly irksome.

You might think that Word–a word processor, after all–would do a better job of this. It doesn’t. They obviously share the same engine. It’s result for this image is identical. I suspect, given that Microsoft has their own popular chatbot, Copilot, that this situation will improve. Having a decent integrated one would save time. But, until it does, there are plenty of options. To make this a fair comparison, I used the same prompt with each bot:

Hey boss. I’m at the Winter Teaching Symposium. I’m presenting later today on accessibility in Word and PowerPoint. I wanted to see if you can generate some useful (or, more useful than Word and PowerPoint) alt-text for the two images I’m attaching. Hit me with your best shot.

Claude

My favorite chatbot, by a long stretch, is Claude from Anthropic. Claude it particularly good at writing and interpretation. It’s the most literary of the chatbots. I suspect they hired some people with humanities backgrounds to work on it, or else they trained it more on literary texts than its competitors.

“Black and white photograph of a man in his thirties or forties wearing a dark overcoat and smoking a cigarette, looking directly at the camera with an intense, contemplative expression. The background is blurred but shows an urban setting.”

That is, in my opinion, a surprisingly good description of the contents of and mood depicted in the photograph.

ChatGPT

ChatGPT, from OpenAI, gave me two options, the first of which it described as “Alt-text (concise, recommended for Word/PowerPoint)”:

Black-and-white portrait of a man in a dark coat looking over his shoulder toward the camera, a cigarette in his mouth, with a blurred urban background.

It described the second option as “Alt-text (slightly richer, if the image supports discussion or analysis)”:

Black-and-white photograph of a man wearing a heavy coat, glancing back toward the camera with a cigarette in his mouth, conveying a reflective, slightly tense mood against an out-of-focus city setting.

I like the addition, in the first version, of Camus “looking over his shoulder.” That captures a bit of the slide-of-life realism of the photograph. And, while it might be a bit over the top, the pic certainly could be taken to convey a “reflective, slightly tense mood.”

Copilot

Copilot, from Microsoft, took the similar, two-track approach we saw in ChatGPT, providing first a “Recommended alt text (concise, effective)”:

Black‑and‑white photograph of a person in a heavy coat, turned slightly away from the camera, with an out‑of‑focus urban background of metal railings and structure.

Copilot also offers a second option, which it says might be useful if “If the image is being used symbolically (e.g., mood, anonymity, introspection)”:

Black‑and‑white portrait evoking anonymity and introspection, with the subject partially turned away against a blurred urban backdrop.

I don’t agree with Copilot’s take on the image as “evoking anonymity and introspection.” But let that go. I’m not sure why ChatGPT and Copilot are giving me two options in the first place. And I suspect the reason their answers are so similar is that Microsoft has a business relationship with OpenAI, the people who make ChatGPT.

Conclusion

As with most literary / humanities tasks, I think Claude does the better job. There’s nothing terribly wrong with the alt text provided by the ChatGPT and Copilot. They just lack a certain style and flow that comes rather easily to Claude. All of them, without doubt, are better than what Word and PowerPoint provided. I’d make a few minor tweaks. While alt text is best when it’s focused on description, not just identification, there’s no reason not to include the the person in the photo, something chatbots, probably for legal reasons, refuse to do. Also, while there’s some dispute about the exact year of the photo, since it was taken in the 1940s, Camus would have been in his 30s. But I think “in the 1940s” is a more useful detail than Camus’ age. So, my version, with those and a few additional tweaks, would likely go like this:

“A black and white photograph of Albert Camus in the 1940s wearing a dark overcoat and smoking a cigarette, looking over his shoulder at the camera with an intense, contemplative expression. The background is blurred but shows an urban setting.”

I think that’s pretty solid. It’s better than my terse, original effort. And it’s better than the raw AI output.

I’ve written a few other articles comparing AI outputs which might interest you: